As many of you know, in August I helped produce a comic book, Sgt. Kroll Goes to the Office, which was highly critical of Lt. Bob Kroll, the current President of the Minneapolis Police Federation. The comic is based, and uses verbatim, a transcript of Kroll interrogating a 14 year old, African-American, boy named Otis, who in 1996 was picked up for riding in a stolen car.

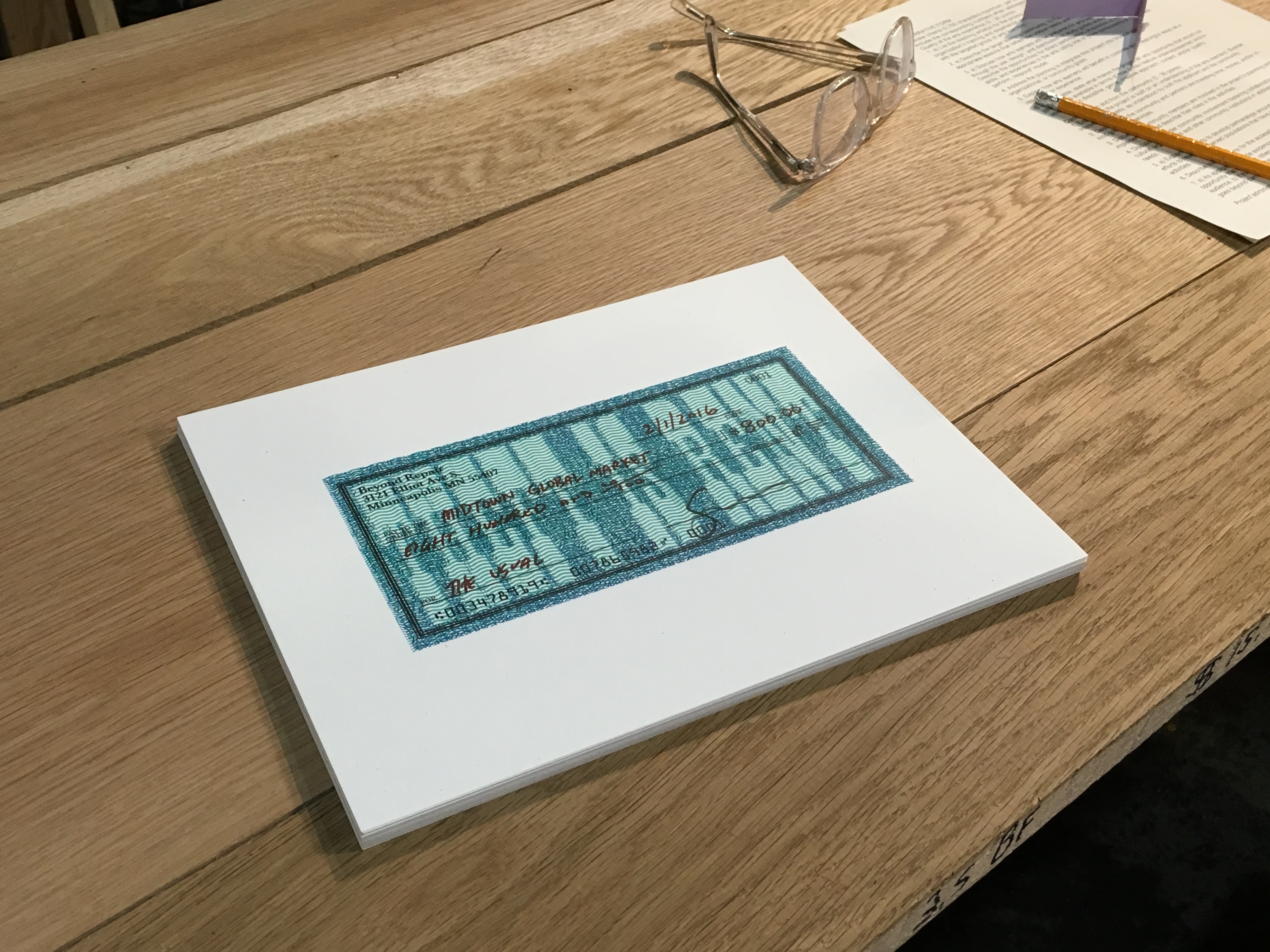

One Saturday afternoon with the help of Tom Kaczynski of Uncivilized Books, we gathered 18 comics illustrators to collaboratively draw the entirety of the transcript, start to finish. Organizing this as a collaborative, and public, effort was highly important to me as it illustrates what we can all do if we come together around an idea. We scanned the files, printed up 300 copies with the equipment at Beyond Repair, and began the process of making a public around this action. After, quite purposefully, hand-delivering the comic to the City Council and the Mayor, we were visited by Kroll himself just a few days later. He came into the shop, grabbed some copies and left without a word. After a series of phonecalls we agreed to meet and discuss the comic and its contents. Yesterday, with the help of a few City Councilers, we met in Room 315 on the third floor of City Hall.

The week and a half leading up to meeting with Kroll, I’ll admit, was intense, confusing, and informative. I had little idea as to what to expect having never met the man before. And from the advice of many who have, I was told I should expect some form of confrontation and to watch my back. I took this advice seriously. I was, and continue to be, appreciative and impressed with the level of help offered to me by friends and strangers alike. I was contacted or in contact with MPD who have past and present knowledge of Kroll, as well as the Department of Justice (amazingly), who felt it warranted to offer mediation if I desired it. I think that says a lot about the level of intensity and scrutiny as regards “Police / Community relations” in Minneapolis right now. When a comic book and the public it is beginning to form draws the serious attention of the DOJ you know “something” is happening. I believe that “something” is a social and institutional landscape which we must – for the health and wellbeing of all Minnesotans, now and into the future – pay deep and careful attention to.

It’s important to note that all my interactions with Kroll up to yesterday morning have been calm and considerate. Yes, maybe it is because I am a 40 year old, decently enough put-together, white dude. But I don’t know that for certain. I’ve been continuously surprised by our considerateness towards one another, and that surprise is something I feel obligated to sit down with and think about further. Yesterday was no different when Kroll and I arrived at the reception desk of the City Council offices at 9am. We chatted and were soon taken around the corner to a conference room. It was just us. No one else was around. And, while I was advised against it, I’m glad in the end it was Kroll and I alone together. The level of privacy was productive. And yet the site, City Hall, at least from my perspective, suggested a degree of publicness that seemed to say we were speaking on behalf of more than just ourselves.

The door closed and latched behind us, we sat down, and very quickly, got into it. Piece by piece we went over the transcript. The “fucks” were flying, and I can attest that, at least as it concerns yesterday morning, I have a far more sailorly quality to my vocabulary than Bob Kroll does. “But that’s fucking bullshit,” was the predicate of a great many of my sentences over the course of the hour that we spoke with one another. Kroll brought up the interrogation method he used with Otis (the Reid method) and I countered that it has been discredited for producing false confessions. He countered that, while that may be public opinion (also the ABA’s!), MPD still spends millions per year sending officers for Reid training. I suggested that that, too, was a problem that needs to be addressed. He made a point of how many run-in’s with cops Otis had, at only 14 years old, prior to their meeting. I said that, from my perspective, that means he needs to be concerned with the trajectory of Otis’s life and the outsize factors which lead he and Otis to meet over the matter of a stolen car. I asked whether he had known about Otis’s homelife. How he had not seen his mother in over four years, and had, for all intents and purposes, “graduated out of” the foster care system. He had not known. I asked him, if he were in Otis’s position and had he lived Otis’s life up till the time they met, what would he want from the authority figure in front of him. What would he need, even if he consciously could not recognize or articulate that need for himself.

To me these are outstanding factors and urgent questions which must be addressed. Then as of now. To many of my questions and concerns Kroll replied, “but that’s not our [the Police’s] job.” And, I’ll admit, I completely agree with him. Police are not greater than, or even equal to, the vast amount of necessary social services and the functions which they are tasked with administering today. The rise of the “authoritarian class,” which discards Care in favor of Order, from Police to educational administrators, is at a historical extreme. We need to consider why and how we have reached this level of peak-control.

It was this point – the outsized role of the Police and their responsibilities – where we found common ground, and I’d argue, provides a wide opening for a sea change within our consideration of the School to Prison Pipeline. With this in mind, one recurring thread throughout our conversation was the radical shift in policing since the time that the narrative in the comic took place and today. While I’m sure there are, and likely will be, continuing disagreements about particulars, both Kroll and I found common ground around the idea that the militarization of the police in the wake of the Clinton Crime Bill and the “war on drugs” has radically altered the role and function of the Police in urban and suburban neighborhoods alike. And that “something” has to change. It is likely the wide berth and ambiguousness within that “something” wherein our differences and ideologies are made most apparent. But I also think, within those gray areas, we, collectively, can find our footing and agreements. Nothing bad, ever, has come out of deciding to take time and respectful consideration across difference. Of deeply listening to the person in front of you despite their past actions. Kroll afforded me that time, and I him. Likely we disagree on about 90% of things. He desires “law and order.” I desire no more cars or roads, the melting down of every gun in America, “artisanal” bread lines, and the abolition of the police and prison system. Basically the complete dismantling of society as we know it. Each of our desires comes with its own unique social and infrastructural violence depending on your inclinations. What exists in the middle so that we might both find the (dis)order and comfort that we need to feel secure and human? To (un)discipline ourselves in the face of one another – as the discipline of our supposed roles is where we violently meet – allows us to recognize our common humanity, or at least provides the opportunity to do so.

How do you come to terms, and strive for collaboration and reconciliation, with someone who you feel (know!) has committed great crimes and violent acts? How do you fairly and equitably engage that question and those histories when those acts are condoned and safeguarded by the State as “legal?” How do you see someone who has, by all accounts, taken part in a system that you feel subjugates and oppresses whole communities, including people you know, love, and deeply respect and care for? What tests must be passed? What agreements must be met? How do you reconcile these histories and their effects without compromising your character or putting others at risk?

For starters, you recognize yourself in them. One of many things that I have learned through Laura from the work that she does is that, not infrequently, she will have to defend someone who has taken part in acts that seem, and in fact are, violently inhumane. But Laura encounters and recognizes the humanity in each and every client she works with. In the interview which I’ve linked to here, which was published, on MNartists.org, the night before Kroll and I met, I wrote:

“From my perspective, there’s always been a very thin line between what is considered the law and what is illegal, between who is ‘in the right,’ and who is ‘illegitimate.’ “

Early on in Laura’s career I had a very hard time understanding or coming to terms with that. But the radical and necessary simplicity of the commitment on her part to see every person she encounters as human, and every role and act as part of a complex system of injustices, has positively affected many lives over many years, mine included.

Outside of my home-life growing up, Kroll and I – it seemed from our conversation – experienced many similar things as kids Otis’s age. I suggested that likely Otis had as well. And yet he experienced wildly different outcomes in regard to his actions. And inasmuch, it’s these disparities which must be addressed. And that both Kroll and I MUST ask ourselves as to why that is. We both agreed that, as kids, we did stupid shit and placed ourselves in situations that should have, could have, gotten us in loads of trouble. But that didn’t happen. Why is that? Those questions – why Otis and not us – need to be considered, and not superficially so. To not engage the complexity of all of our roles within injustice perpetuates injustice. And so, for me, the answer to the question of why Otis and not us is simple. Otis was poor, and Otis was black, and for as long as the Policing system has existed in the United States as we know it those two distinctions have been – by design – criminal in nature. We cannot allow or make excuses for that. It cannot simply exist and be perpetuated because it is our job. Our “discipline,” as it were. It is not simply wrong, or unjust to do so. It is inhumane.

And so, within all these complexities and considerations, contradictions and hypocrisies, yesterday I encountered a person who is willing to listen and respond sincerely and honestly when afforded a considerate amount of respect. Maybe yesterday was an anomaly, but I am willing to think otherwise. I can understand the impulse to be dismissive and aggressive in the face of the opposite of respect. I’ve felt that way throughout my entire life. When someone treats me like I am worthless I want to, at best, sabotage that relationship, at worst punch them in the face, and in the darkest recesses of my heart something far worse. Those impulses lie at the center of our collective conversation. When an occupying force patrols your neighborhood, and you feel as if you are seen as the enemy, how do you respond? I know how I respond, and I am not seen as a threat within that larger narrative. I get a pass. What happens to those who do not? Who act, while impulsively, naturally to being treated with disrespect?

There was one occasion, when Kroll caught himself discussing neighbors, citizens, as if trapped in an “Us V. Them” scenario, and completely unprompted he stopped, and corrected himself. Not out of propriety, or politics, but self-concern for what that meant to him and others not like him. He said, “that’s not what I mean. I don’t want it to be that way.” While a long way off, I think mutual respect and compassion between Police and neighbors can be met. And I think Kroll sincerely desires that as well. But that respect is contingent on a very important factor. As I mentioned to him on numerous occasions throughout our conversation: “but I don’t have a gun.” On any and every occasion the presence of a weapon is going to make the levels of respect within a relationship violently out of balance. And inasmuch, it is up to the police to do MORE than their share of the heavy lifting.

To my surprise and enjoyment the Bob Kroll that I encountered yesterday was not the blustering, aggressive stereotype that I have witnessed through the press. And there were moments that I think I might have broken the mold for him as well. He was not the person I expected to meet. And, possibly, neither was I for him in return.

Again and again he represented positions and stated beliefs which made me respond, “But, Bob, I have NEVER heard you say anything like that in public.” And his response was almost always that if he tried to no one would listen. To some that statement might seem insincere, but I take him at his word. I do think that Kroll wants to do good (as he sees it), and that every step of the way, all the coverage he gets is bad. That the negative aspects of his role within MPD – aspects which must be reconciled with – are the only coverage which he receives. I am not here to say that Kroll has been “misunderstood,” but I am here to listen to more than soundbites.

On each of these “say that in public” situations I urged Kroll to do just that and offered to assist in augmenting and instrumentalizing that voice and those perspectives. I suggested that budgets could be spent differently to positively affect both the safety of Police as well as the well-being of neighbors and neighborhoods, and he agreed. I can only wonder, in such a divided city as Minneapolis, what could come out of conversations such as the one Kroll and I had yesterday if they were public, spirited, accountable, and collaborative. Let’s say, “Un-Minnesotan” in character. Despite our differences, what could arises out of agreements that seek to care, protect, and nurture all the people who inhabit the shared social landscape which we live upon? I asked Kroll if he would be willing to have conversations like that again, and to have them publicly? I said they would likely be contentious, and at times very heated, but that at the end of each one of them, if we truly meet across difference with the intention to recognize one another as human, we will leave those conversations shaking hands and agreeing to meet again. He said yes.

I am going to hold him to that. Red76 has a project taking place at the Mia for two months which begins in November. The role of the project, entitled “Yes, and…” speaks precisely to what we can encounter between stark differences. Between “Law and Order” and “Revolution and Revolt.” To paraphrase James and Grace Lee Boggs, it will take “evolution” for us to collectively reach that new social landscape. Our time at Mia looks to consider how we can engage the deep hurt, violence, and disregard which surrounds our lives together in a space outside of crisis, and response and offer up a different manner and method of living together outside of discipline and punishment, confrontation and dismissal. I hope he accepts the offer to speak again. And I hope that many many others will join us. All you need to do is step forward and the space is yours.

Even just two days ago I would have challenged you to convince me that I would walk out of a meeting with Bob Kroll with a continuing level of regard and understanding for him. There is still much that I need to reconcile, but any and all encounters or confrontations with him, for my part from here on out will be met with a healthy dose of mutual accountability and respect.

It is much easier to have an adversary. When we are “in the fight” we have someone to blame when we lose, or are knocked off guard. With an enemy we are easily afforded the out of not looking deeply at how we all – and I mean, sincerely, ALL of us – got here. Outside of the highest reaches of power and authority, down here living our lives together, I do not believe that anyone is inherently evil despite the violence they may commit. As I said to Kroll yesterday, “We are all racists.” I could add to that we are all scared, envious, contemptuous, and at times cruel and unthinking. But we are so much more, and often so much better. No one is inherently evil. But I do believe we are aggrandized into positions which allow us to do evil things and see ourselves in the right. It is up to us to always, again and again, knock one another down from positions of authority. Not as attack, but as a way to see eye to eye. The first stage of this action – the publication of Sgt. Kroll Goes to the Office – was, indeed, an attack. What I have realized after meeting with Kroll is that it doesn’t need to continue to be. It is now an invitation, continuously extended, to make things whole. To recognize one another. To call into question who is really in charge, to whose benefit, and to what end. Despite the many, many people who will see this as capitulation, I urge you to think about the deep seated reasons why you might want to continue having an enemy when, with long and painful work you may, sincerely find a common partner in a different world than the one we know right now. How do you fight a war – and that is precisely what we all, on the ground, are in the midst of – if the enemy in front of you is no longer your enemy and yet the effects of the war continue? Where is the fight?

At the end of the American Revolution, when Corwallis surrendered to Washington, the British Fife and Drum Corp. was instructed to play And the World Turned Upside Down, of which the first verse reads:

Listen to me and you shall hear, news hath not been this thousand year:

Since Herod, Caesar, and many more, you never heard the like before.

Holy-dayes are despis’d, new fashions are devis’d.

Old Christmas is kickt out of Town.

Yet let’s be content, and the times lament, you see the world turn’d upside down.

I am all topsy-turvy. I will no longer fight Bob Kroll. But I will give him hell every step of the way and continue to do so. I hope and expect him to do the same. And I hope I am not alone. The only thing I have ever desired in my life is the continuation of the belief that “another world is possible.” When the opportunity presents itself, when a door opens that offers the possibility that that “other world” may exist if I step into the unknown, I have to go there. We should all go there, despite the very real dangers we might encounter along the way. There’s safety in numbers.

In the two weeks since we distributed the comic I have felt the need to change my route home from the shop nightly, at risk of getting attacked on my way. I have worried about the safety of my family and the well-being of my children. I have been worried about retribution against people I know and love who have any association with me whatsoever. I have been conscious of little else except the ambiguous and ever present notion of “threat.” And now, after my meeting with Kroll all of that is gone. I no longer feel that way. In fact I feel that there is someone, if I confront them or if they confront me, who will listen. Violence has been replaced by passionate disagreement. A person who, despite our differences, sees me as human. What we must come to terms with, and why we must keep working and talking and planning and shaping new ways to encounter one another humanely, is that there are literally thousands of others living in Minneapolis who, every day of their lives, justifiably feel as I have felt. And there is no prospect presently presented to us to alleviate that very real threat. That very real and very deadly physical and psychic assault upon their bodies, communities, histories, and traditions. There is safety in numbers and it is up to us to grow our publics. Through methods known and unknown, tested and untested, for anything nourishing to take root.